On Bias

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17122595

The contemporary moment seems to be one of “enchanted determinism”1—a constructed belief that technology will inevitably find the right answers if fed enough data. Yet the principle of “garbage in, garbage out” remains as relevant as ever. The “garbage” in this equation increasingly takes the form of bias, resulting in algorithms that discriminate against marginalised populations and systems that reproduce harmful content.

This challenge is compounded by multiple intersecting forms of bias such as in source (selection), interpretation, representation, and algorithms. Despite growing attention to ‘bias mitigation’, the term carries different meanings across disciplines, complicating systematic approaches. This conceptual instability, if left unexamined, has the tendency to render bias both omnipresent and at a risk of becoming meaningless.

One-sided tendency of the weighted ball¶

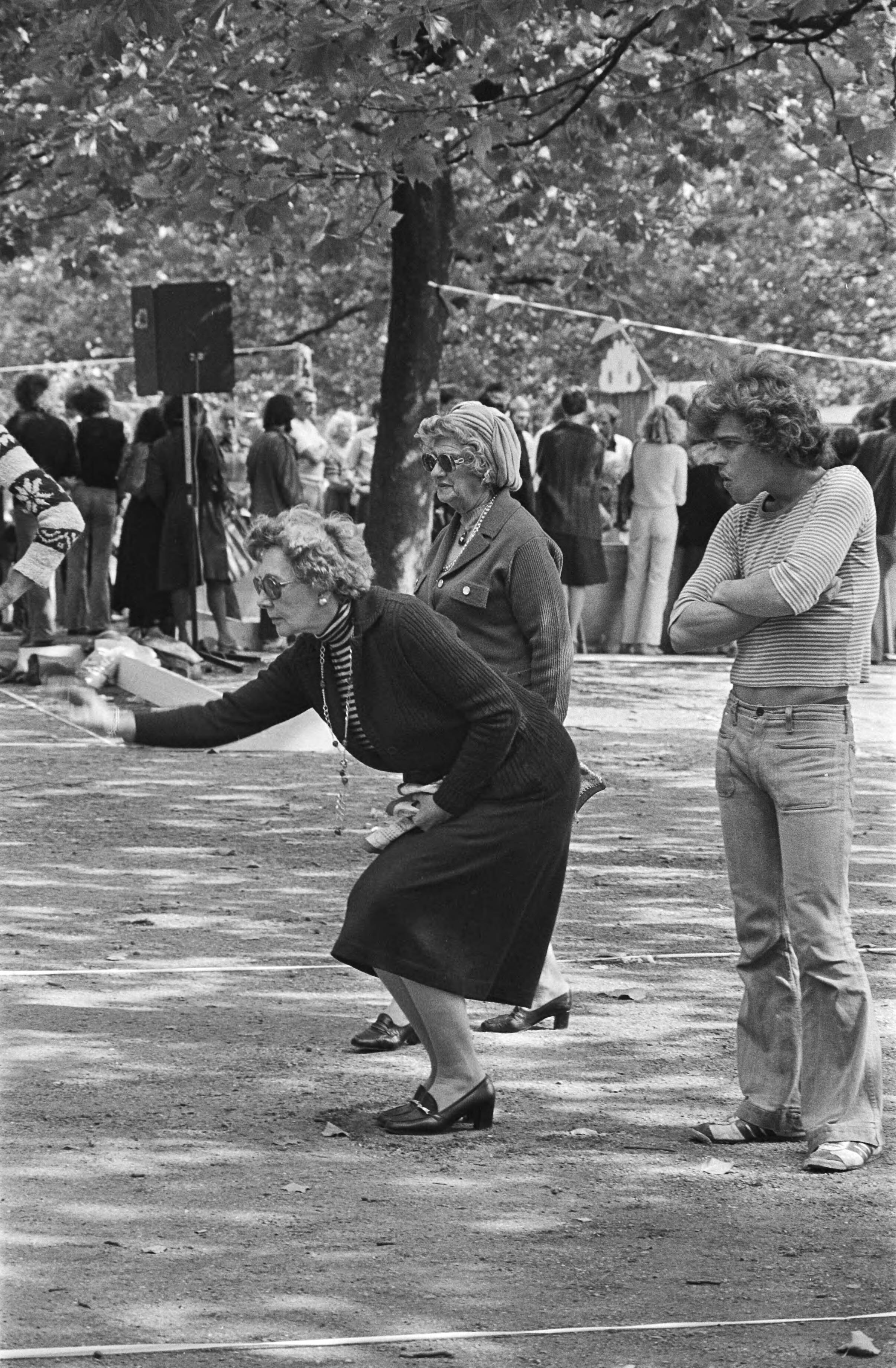

To begin conceptualising bias, we first turned to its etymology. “Bias” first entered the English language in the 1570s as a technical term from the game of boules to refer to balls weighted on one side, causing them to curve obliquely. From this emerged the figurative sense of “a one-sided tendency of the mind” and later “undue propensity or prejudice,” particularly in legal contexts. The French origin biais means “sideways, askance, against the grain”—suggesting movement contrary to an expected direction.2 Some etymologists trace it to Latin biaxius (“with two axes”).3

This etymology prompts a critical question: when we designate something as “biased,” what is the assumed “true” path? What constitutes an unbiased space, description, or archive—and is such a thing even possible?

The textile metaphor¶

Rather than pursuing an illusory “bias-free” ideal, we find inspiration in another meaning of bias: in textile, bias refers to fabric’s diagonal stretch between straight grains, the warp and the weft—where the material shows greatest flexibility. Garments—such as a tie, dress, or skirt—cut “on the bias” follows this diagonal orientation, creating fluidity and adaptability in the finished piece.

We leverage this sense of bias in our framework: just as fabric’s bias exposes structural tensions and possibilities, biases in datasets highlight gaps, conditions of production, overlooked questions, and unconsidered perspectives. This transforms bias from a problem to fix into an investigative lens or a “category of analysis”. 4

Bias as Heuristic¶

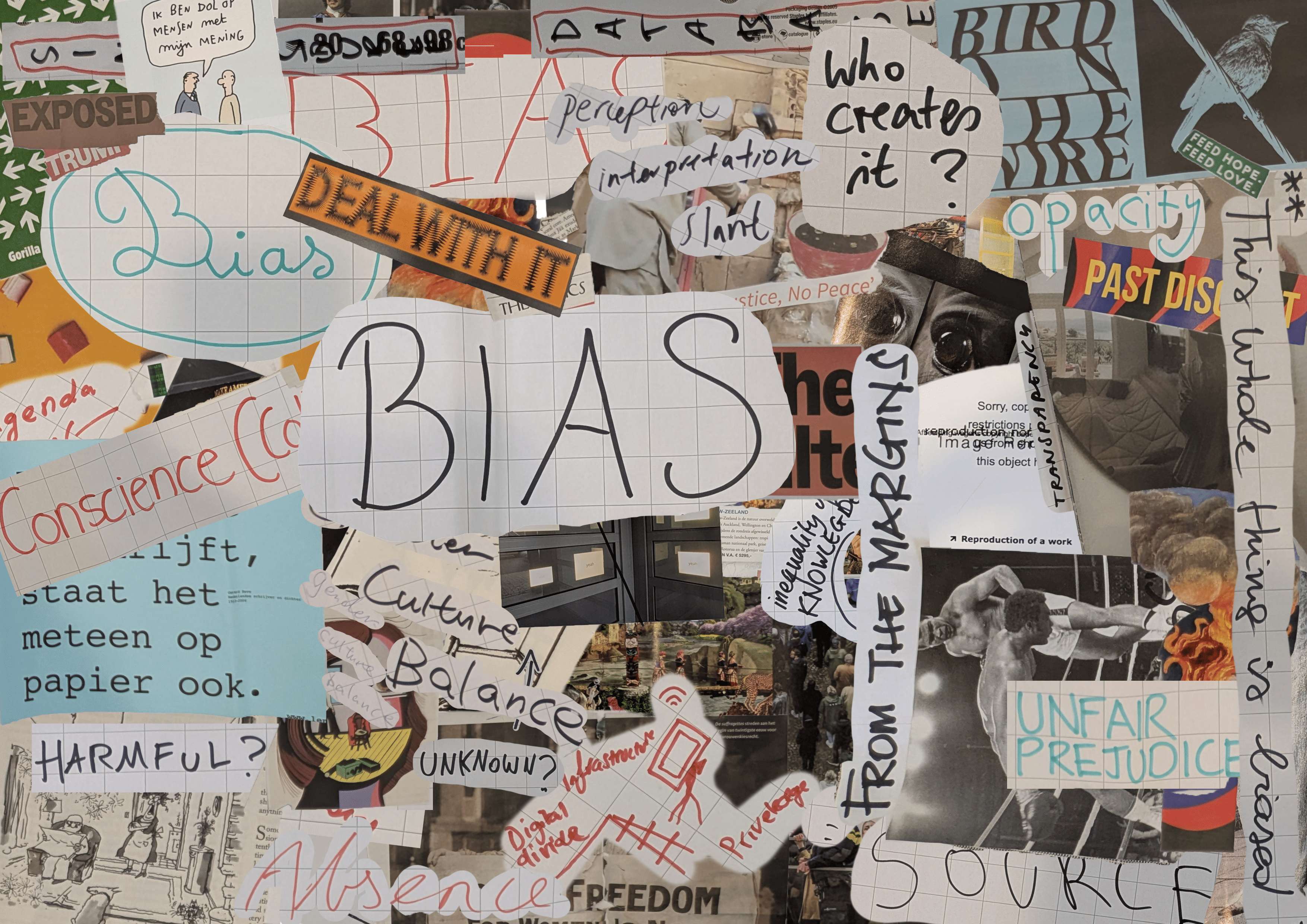

Instead of searching for one definitive meaning, our research reveals that bias functions as a heuristic—a shorthand referring to a web of interconnected concerns relating to power, inequality, positionality, silences, knowledge, and representation. This research consisted of our interviews with dataset creators, researchers and practitioners, literature reviews, and collective creative brainstorms (resulting in Bias(ed) Maps). The latter, especially, represents the complex and multi-layered nature of ‘bias’.

Rather than forcing these into a single definition, we are developing a ‘bias vocabulary’ that maps these concepts, visualises their connections, and places them within the dataset lifecycle.

-

Campolo, Alexander, and Kate Crawford. “Enchanted determinism: Power without responsibility in artificial intelligence.” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society (2020) ↩

-

Scott, Joan W. “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” The American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (1986): 1053–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/1864376 ↩