Reflecting on Bias: Lessons from the VOC Data Experience¶

Written by Lodewijk Petram

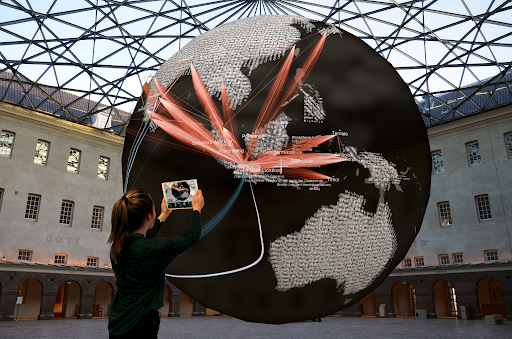

Historical datasets are never neutral. They are shaped by the contexts in which they were created and often reflect the biases and silences of their time. Working with such datasets requires not only technical skill but also a critical awareness of their limitations. This realization became especially clear to me through my work in 2020-2021 on the VOC Data Experience, a museum installation offering six data-driven augmented reality experiences about the Dutch East India Company (VOC) that toured the National Maritime Museum in Amsterdam, the Rotterdam Maritime Museum and the exhibition space of the Dutch National Archives.

Confronting a Controversial Legacy¶

The VOC is a contentious topic in Dutch history, sparking extensive debate. Once celebrated as an innovative trading company symbolizing national pride, it is now mainly critiqued for its exploitation, slavery, and violence. The VOC Data Experience sought to engage museum audiences with this complex past, encouraging them to reflect critically by exploring the company’s historical data. Our goal was not to dictate narratives but to present raw data in compelling visualizations, allowing visitors to discover stories and form their own interpretations. However, as we delved deeper into the project, we encountered the limitations and biases within the three major datasets that we used:

- VOC Opvarenden: A dataset of 774,200 VOC payroll records, published by the Dutch National Archives.

- Dutch-Asiatic Shipping (DAS): Data on VOC voyages between Europe and Asia, published by the Huygens Institute.

- Bookkeeper General Batavia (BGB): Records of trade through Batavia (now Jakarta), also published by the Huygens Institute.

Each dataset, though rich, is shaped by the biases inherent in the VOC’s administrative machinery. These datasets exist because the VOC meticulously documented aspects of its operations aligned with its bureaucratic and commercial priorities, and these documents were subsequently preserved in the archives. For example, the VOC Opvarenden dataset reflects the payroll system, including only European crew, while ignoring the many Asian workers crucial to the VOC’s operations. Similarly, the BGB dataset omits private trade by VOC personnel (which was permitted to some extent), VOC trade bypassing Batavia, and, crucially, trade conducted by Asian merchants on the same routes. These gaps highlight how the VOC’s perspective—rooted in its administrative priorities—frames what is visible in the data and what remains obscured. This perspective has also shaped the creation of datasets and the focus of researchers, with disproportionate attention given to topics like Dutch shipping, largely due to its overrepresentation in existing sources and datasets. Consequently, the path dependency created by these archival biases continues to shape the trajectories of research.

Designing for Nuance¶

Presenting such biased datasets to a general audience posed a challenge. How do you make these limitations clear without overwhelming visitors? How do you encourage critical reflection without lengthy explanations? Our solution was to create visualizations paired with audio guides. Each experience features a conversation between me, as the data expert, and a historian or heritage specialist. These experts provide context and highlight what the data includes—and, crucially, what it omits.

For example, the experience around the question ‘Did the VOC trade enslaved persons?’ addresses the almost complete invisibility of enslaved individuals in the VOC records documenting trade through Batavia, explaining how much of the slave trade was carried out privately by VOC employees and thus escaped official documentation. Through these dialogues, visitors gain the tools to interrogate the data, understanding not just what it reveals but also what it conceals.

Implications for Combatting Bias¶

It was inspiring to contribute to the development of the VOC Data Experience. While I’m accustomed to working with datasets and exploring how they can answer research questions, this project required a different mindset. We needed to craft thought-provoking questions and compelling visualizations tailored to a museum audience. And with just three minutes of audio for each experience, we had to guide visitors through the explanations while also addressing the biases, silences, and limitations inherent in the datasets.

Even though I was already familiar with these datasets, collaborating with experts from diverse backgrounds brought fresh perspectives, uncovering biases and gaps I hadn’t previously noticed. For instance, one of the topics we explored in an experience was women in the service of the VOC. This was based on records from the VOC Opvarenden dataset, which document cases where individuals were removed from service upon being identified as women, as noted in the original pay books. While I had thought about how these situations might have been handled, I hadn’t deeply questioned the nature of these records. Dyonna Benett, however, did. She noted that while the VOC classified these individuals as women, they may have identified themselves differently. Her insights, along with those of other experts, often challenged my assumptions and underscored the importance of diverse perspectives in interpreting and understanding historical records.

The lessons from this project resonate with the goals of the Combatting Bias project. As we work toward drafting guidelines for equitable data collection, the VOC Data Experience demonstrates the importance of contextualizing data to reveal its biases and silences, incorporating multiple perspectives in the interpretation process, and engaging diverse audiences to broaden our understanding of historical records.

Bias in historical data is unavoidable, but by confronting it directly, we can use the data to tell richer, more inclusive stories about the past.